Build to matter

Ready to work together?

If you’re ambitious about growing a business that matters—and resonate with our approach—we’d be delighted to talk.

History’s cycles often end in collapse. But collapse can mean transformation. With AI multiplying possible futures, the question is: how do we craft it well?

Emma Walford

September 16, 2025

Tytler’s cycle is said to chart a civilisation’s rise and fall through nine (repeating) stages: bondage, spiritual faith, great courage, liberty, abundance, selfishness, complacency, apathy, and dependence. It’s widely attributed to Scottish historian, Alexander Fraser Tytler (1); however, despite being Scottish myself I hadn’t heard of it until I read my stepson Tom’s essay competition submission: ‘To what extent is our civilisation in danger?’.

His essay won the competition. And, although that was over a year ago, it sprang to mind recently as I listened to various debates about AI’s increasing influence on our future – particularly the potential emergence of artificial general intelligence (”AGI”) or even superintelligence in the next decade.

Quick sidebar: AGI refers to a hypothetical form of AI with general cognitive abilities comparable to humans, able to perform any intellectual task across domains. Superintelligence is when those capabilities far surpass ours.

Digging deeper into the (previously unknown to me) Tytler, there are some important caveats before we go further. Firstly, Tytler’s cycle might not even have been Tytler’s. Historians argue it’s rhetoric more than scholarship, and there are many other models of rise and fall.

Different thinkers, different data, different emphases. Yet they all share the uncomfortable conclusion: civilisations decline. Growth leads to abundance, abundance to complacency, complacency to collapse. Whether that collapse is always terminal, or can sometimes be transformational, is something we’ll come back to.

So, for the sake of a framework to structure our thinking, let’s stick with Tytler’s. And start with the obvious: where in the cycle are we today?

If Tytler’s cycle holds, today’s West appears to sit on the cusp between apathy and dependence. Tom’s essay reached the same conclusion.

Anecdotally, I can think of dozens more signs. The helplessness felt by many of today’s graduates, with diminishing hope of jobs and home ownership. The way that nobody in London reacts when they see someone’s phone get nicked. Our falling birth rates.

Historically, this stage of the cycle represented dependence on human rulers and increased reliance on the state. Today, I think we need to look also at the real possibility of dependence on non-human powers.

So, habits of reliance are forming. The question is whether government, tech-bro bosses or bots are waiting to restrict our civil liberties and pull the strings when we get to the finish line.

A sculpture honouring map-reading by Virginia Knight

If that’s where we are, a quick look in the rear-view mirror helps explain how we ended up here.

Arguments vary on when our current cycle began. It’s said that Tytler’s cycle – or the lifespan of democracies – lasts an average of 200 years. That seems to be folklore, but let’s roll with it and map our current cycle, starting around the middle of the 19th century.

History suggests cycles often end badly – but not always.

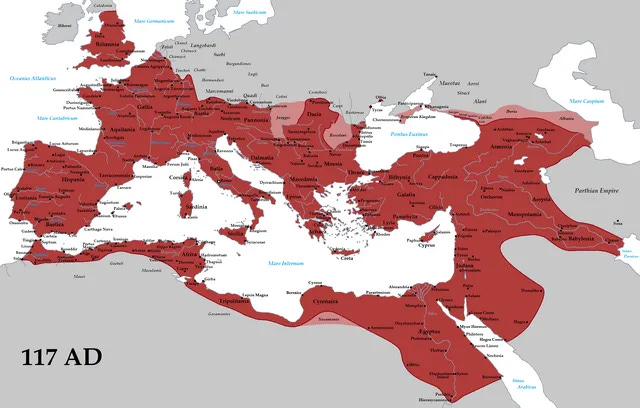

Rome is the archetypal example of a civilisation sliding back into bondage. After abundance (for many) corruption and complacency set in, leading to apathy and dependence on local warlords and kings.

Ancient Egypt offers a similar story: the abundance of monumental construction, heavy tax burdens, a loss of engagement, economic decline, political fragmentation and eventual subjugation by foreign powers. Unlike Rome, Egypt didn’t vanish, showing that transformation is also possible at end-of cycle.

History offers up other examples of cycles that have been disrupted…or have undergone positive transformation at the point of collapse.

The past, then, shows societies often collapse, but can also – in the process – transform.

If our cycle continues unbent, we appear to be looking at impending collapse into bondage. But to whom will our shackles be tethered?

Alternatively, something will happen to bend our cycle. That could be good, or existentially bad.

Should we try to avoid collapse or accept it? Should we fear bondage? Are our outcomes worse or better under machine rule? These questions - which would recently have felt like sci-fi – feel like reasonable things to consider.

If collapse is where we’re naturally headed, how do we craft it – towards more positive and transformative outcomes – rather than hoping the cycle will miraculously bend.

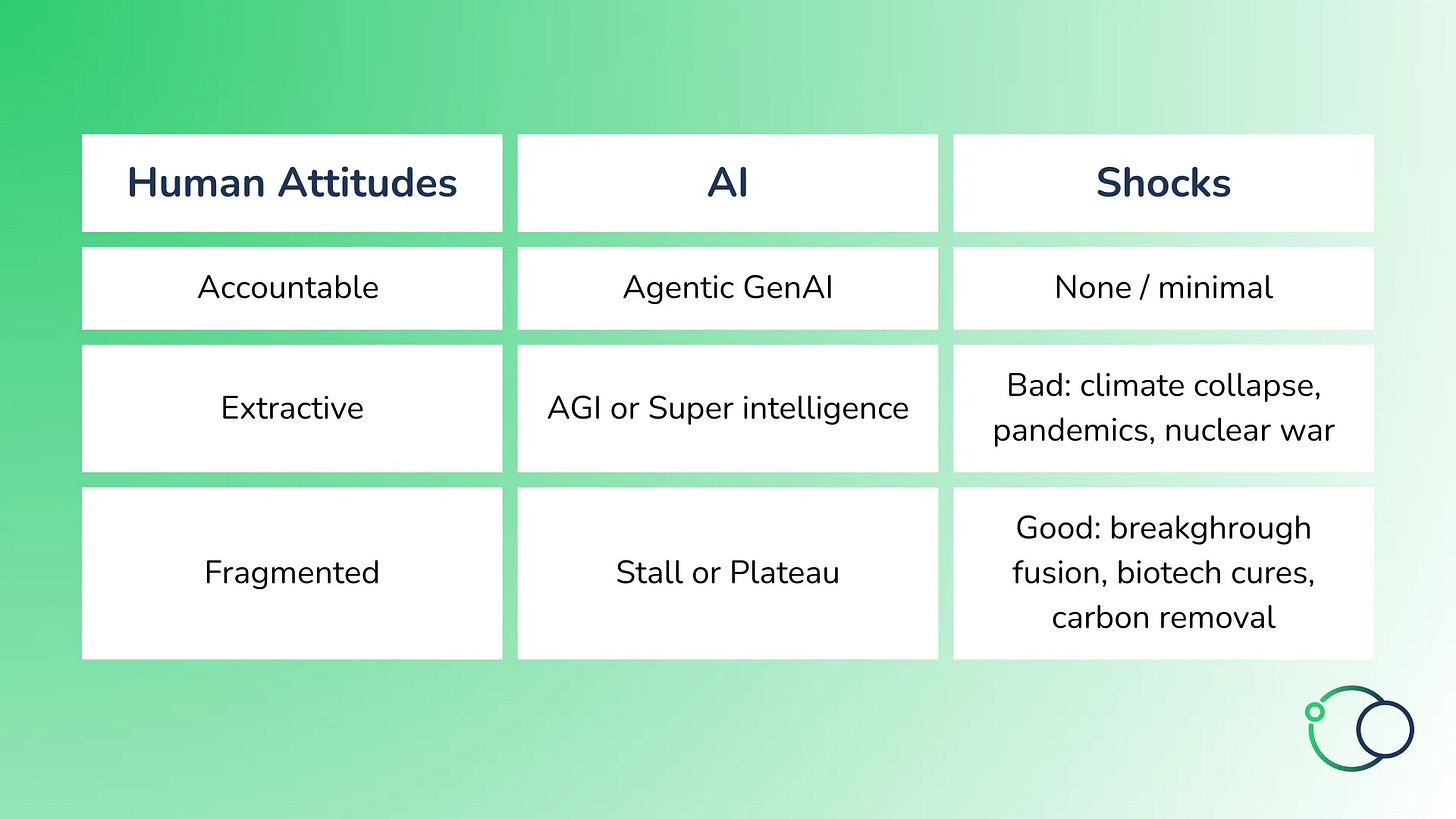

Here’s a game I’ve developed for scenario planning. Pick one row from each column and paint a picture of the future that could bring.

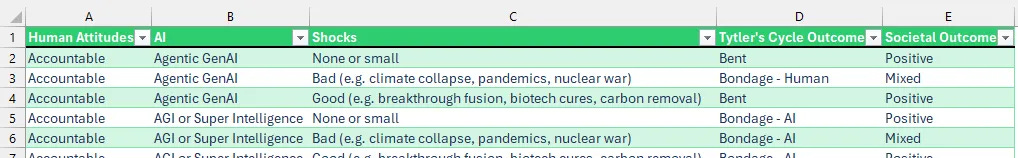

In the old world, there was no AI column and 9 high-level futures. With AI in the picture, we have 27 possible high-level futures. For each, we can assign a likely outcome about Tytler’s cycle (”bent”, “bondage to humans” or “bondage to AI”) and for human society (”positive”, “mixed”, or “negative”).

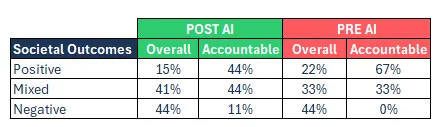

Keeping things basic and equal-weighting the futures and their outcomes:

The equal weighting is deliberate: an accessible provocation tool, not a complex probability model. In practice, some futures are more likely than others. But simple arithmetic demonstrates an important point: the arrival of AI doesn’t just add another option, it multiplies the possibilities. And turns up the stakes on human accountability – “Accountable” attitudes could raise the probability of a positive future to 44% (again, on overly-simple maths).

Which takes us from arithmetic to action.

This isn’t about prediction – that’s increasingly pointless.

The grid offers a way for leadership teams to practice uncertainty. To stretch their strategy muscles: play to loosen thinking, bravery to sit with uncomfortable futures, long-termism to extend horizons and humanity to keep what matters most front and centre.

When we run this kind of exercise with teams, the numbers are simply the start of the conversation: Which futures feel most plausible? Which most uncomfortable? Which worth working towards? Is it worth worrying about an AI master?

What choices could we still make today to bend the cycle or steer society’s collapse towards a world we still want to exist in?

For leaders, this exercise raises questions like:

If we don’t carve out time for these questions, we slide further into apathy and dependence.

Making space for quiet contemplation and wonder is not to scare ourselves, but to make peace with what we can’t control and focus on what we can.

The more we do, the greater chance we have of steering away from an inevitable-feeling decline and towards either a bent cycle that works in humanity’s favour, or even a state of “bondage” to a new AI or human master that expands, rather than diminishes, human potential.

And if we can get these conversations out of the boardroom and into our homes, even better. This whole line of questioning started with Tom’s school essay, ‘To what extent is our civilisation in danger?’. That’s exactly the sort of long-term, big-picture debate we need more of – in schools and homes. If the next generation is already asking bigger questions, the least we can do is take them seriously – and answer with bigger thinking.

Sources

Creative Commons license link for images:

TL;DR: Civilisations tend to rise, peak, and decline - but AI adds a new twist, multiplying possible futures. History shows collapse isn’t always catastrophe; it can be transformation. The real question is: what kind of future do we want to craft? For leaders, that means carving out time for long-term, accountable, human-centred choices before the cycle drags us into collapse.